John Vanderpant photographs with both reverence and curiosity. Born Jan van der Pant in the Netherlands in 1884, he arrived in Canada in the early 1910s and quietly began building a body of work that still shapes how we see Canadian light, industry, and landscape. He was equally poet, scientist, and artisan, using his camera not just to record what lay before it, but to translate what stirred inside his mind.

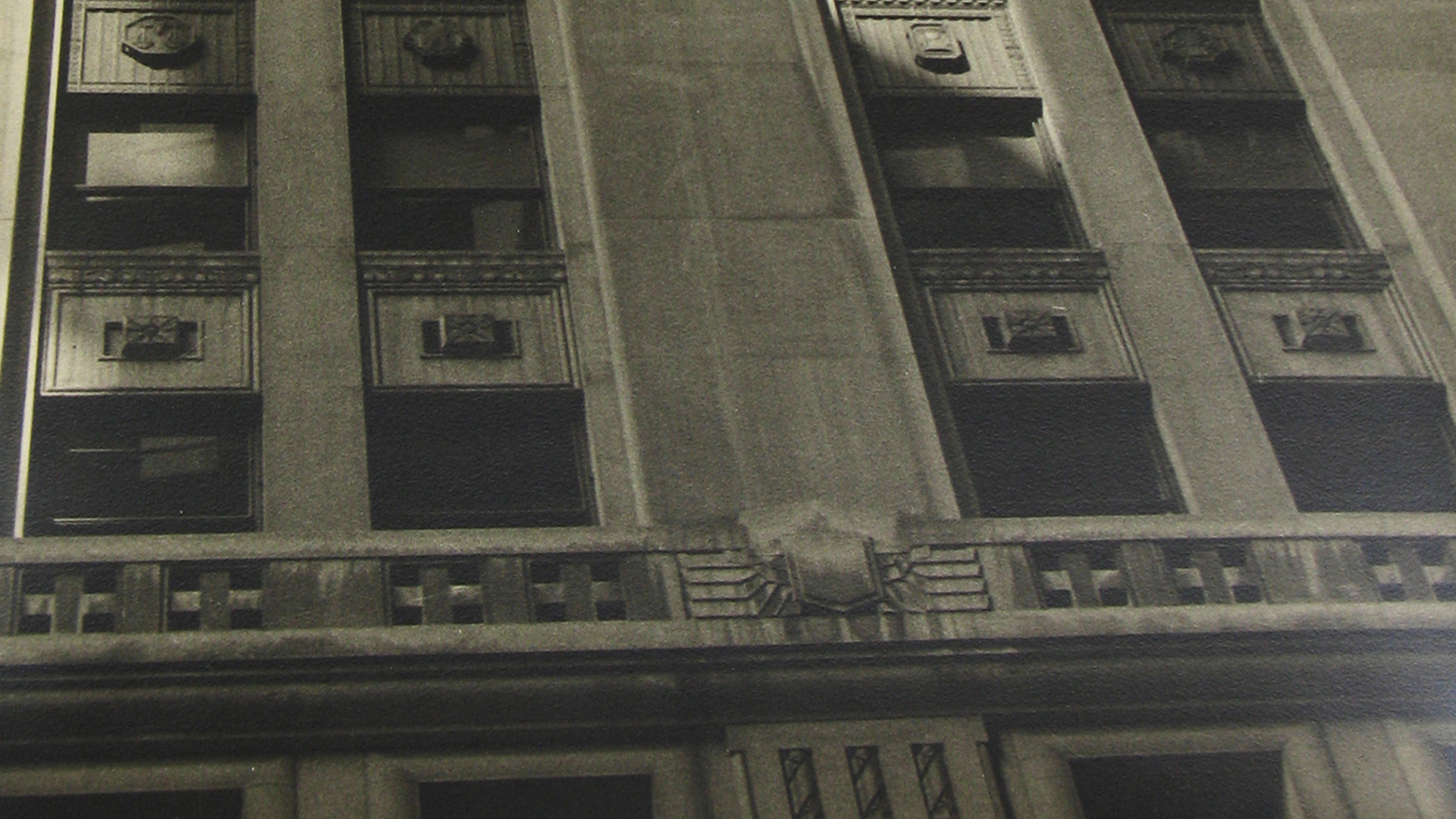

From small towns in Alberta to industrial Vancouver, Vanderpant’s eye moved between the micro and the monumental. His early work—portraits, landscape studies, delicate still lifes—showed Pictorialist softness: gentle focus, textured print surfaces, dreamy light. But as his vision matured, he grew drawn toward architecture, industry, and the rhythms of Canada’s growing modern identity. Grain elevators, railway stations, even cabbage blossoms became motifs to explore form, symmetry, and shadow.

One of his most iconic images—Temples of Today—renders towering grain elevators as sacred geometry. In that photograph, the concrete and steel becomes sculptural; light angles between structures, lines converge. It’s as much about what the photograph frames as what it excludes. Vanderpant achieved this not with harsh manipulation, but through respect for shape, form, and contrast.