Sometimes childhood pain doesn’t announce itself with cries or tears — it hides under the hot sun, in the restless silence of a swimming pool. That’s the haunting world of A Crab in the Pool, by directors Alexandra Myotte and Jean‑Sébastien Hamel. In eleven minutes of hand-drawn animation, we follow siblings Zoé and Théo as they navigate grief, memory, and the fragile bonds that try to hold them together.

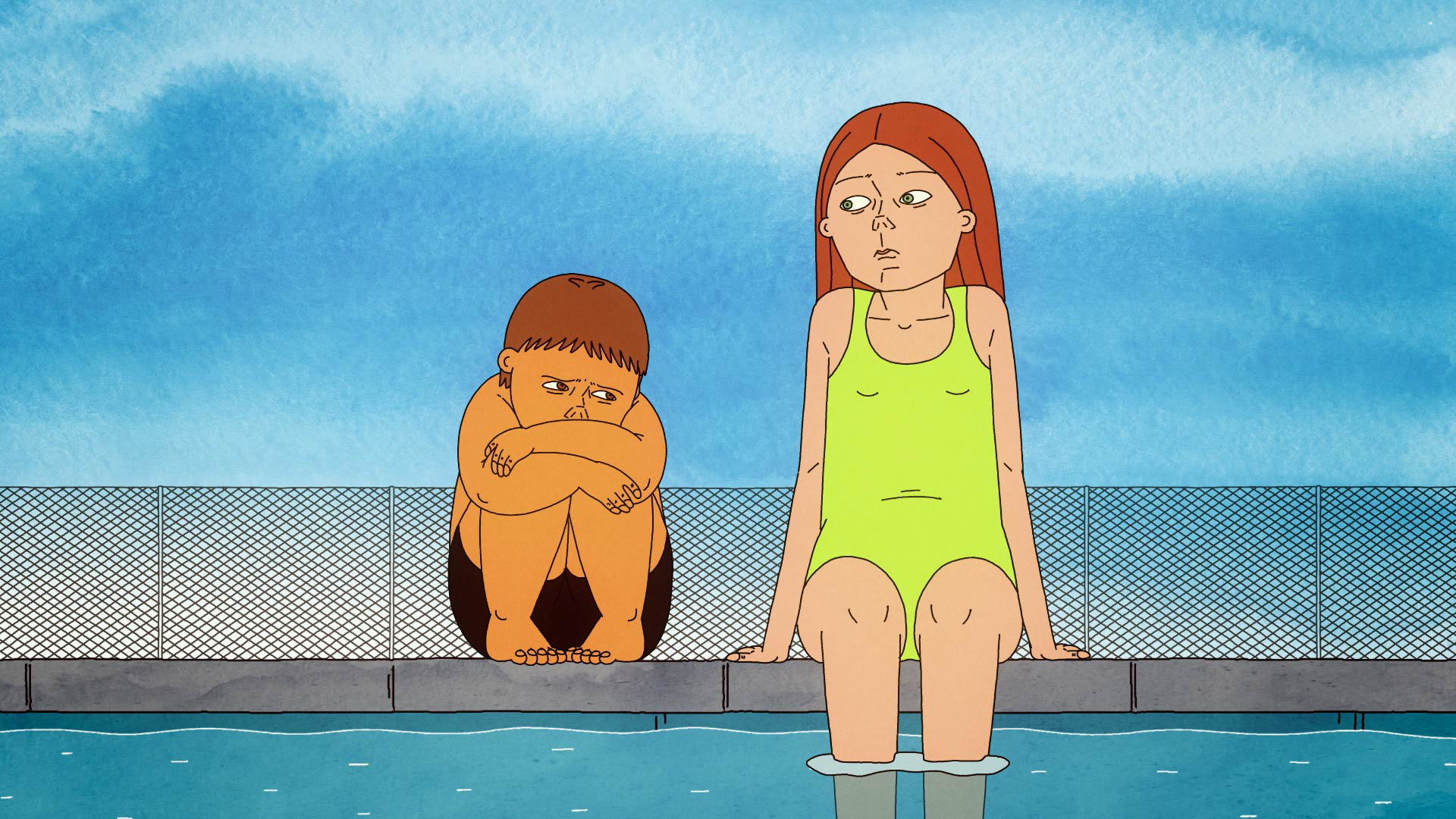

Set in a worn-down Montreal neighborhood during a sweltering summer, the film opens on Zoé — a teenage girl carrying anger and unspoken fears. Her younger brother Théo seeks refuge in fantasy. When they go to the public pool, their grief surfaces not through words, but in visceral, surreal visions: Zoé hallucinates a crab emerging from her chest, a metaphor for the pain she can’t name. Meanwhile, Theo slips into a mythological world through his “pretend binoculars,” reimagining ordinary people as creatures from his coloring-book mythology.

What makes A Crab in the Pool so powerful is its balance between harsh reality and imaginative escape. The animation style — soft, fluid, and deceptively simple — doesn’t try to prettify pain. Instead, it gives space for subtle emotions, letting grief, anger, confusion, and longing surface through color, movement, and metaphor. The editing plays its own role, blurring the line between what’s real and what’s imagined, as memories and fantasies collide.

By the end, Zoe and Théo share a quiet moment of understanding: they might never fully heal the wound that looms inside them, but acknowledging it — together — is a beginning. The film doesn’t promise redemption. It offers solidarity, showing that grief doesn’t always need words, just presence, and shared recognition.

A Crab in the Pool reminds us that sometimes the deepest scars are invisible to eyes but alive in our bones — and that healing often begins when we let the unspeakable take shape.