A latest travelling exhibition, Patterns & Parallels: The Great Imperative to Survive, brings together images of threatened bird species and their migratory corridors. The work collates three perspectives—surface, aerial, and space—to show how habitats, flight paths, and Earth’s changing face intersect. There’s a gravitas in how she layers these views: a crane or flamingo might appear small in one frame, monumental in another, and ethereal in space-born maps. What carries across all scales is urgency—the responsibility of seeing what might be lost.

Bondar’s technique reflects her dual life as scientist and artist. As a young photographer she trained using fluorescence, electron microscopy, and craft-based printing methods; today she marries technical precision with poetic framing. Colors are rich but controlled. Light doesn’t just illuminate—it sculpts. Her landscapes are not passive; they ask us to inhabit their edges.

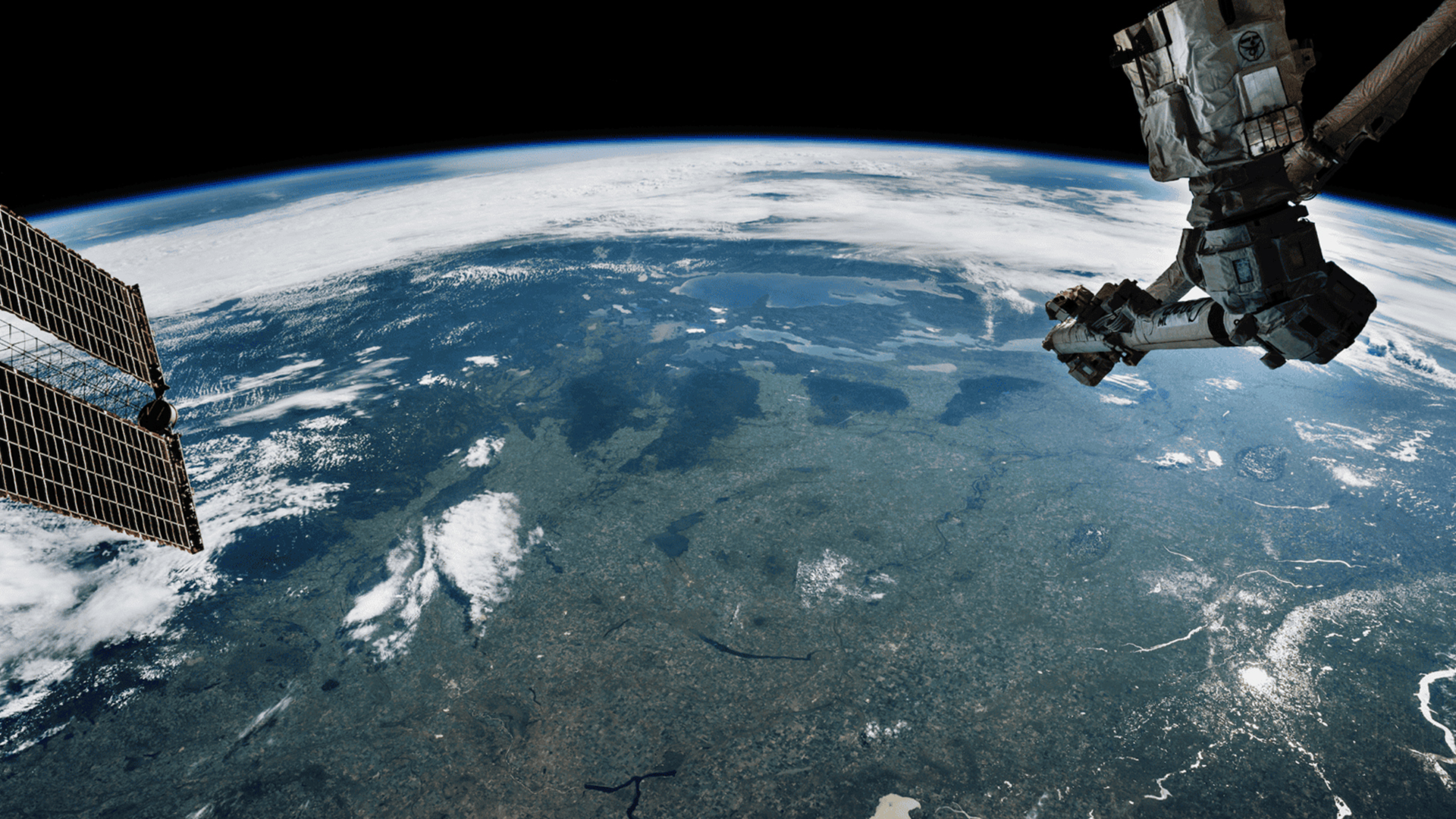

In Canada—where geography can stretch forever but climate and ecosystems are increasingly under pressure—Bondar’s work feels especially essential. An exhibition marking the 25th anniversary of her space mission revisited the Earth she first saw from orbit—not to romanticize, but to re-inscribe that moment of perspective into current debates: conservation, biodiversity, environmental ethics.